Within days after launching Transgasm.org to “change the way surgeries are funded in the FTM and MTF communities forever,” Jody Rose and Buck Angel shut down the website amid criticisms that its scheme was untenable and illegal. The website now states: “We are disappointed that there are people who are spreading false rumors and slandering our names all over the internet. […] Because of this, we have chosen to remove ourselves from a project that is dear to our hearts.”

Rose and Angel repeatedly assert that their intentions were “good and genuine.” As I’ve pointed out in my previous posts, that their intentions may be “good and genuine”–as opposed to sinister and malicious–is precisely the problem.

In the now-deleted “Transgasm FAQ,” founders discussed how Transgasm was inspired by “law of attractions”:

The both of us have been corresponding for years and share a common interest: The law of attraction and thought science. We’ve always shared stories about how we’ve manifested what we wanted throughout the years, using thought science and the law of attraction.

One day we were talking about this again and realized that we could help empower the entire transsexual community (worldwide), its supporters, and anyone else who identifies the way they choose to identify, by sharing our success with thought science and the law of attraction. We worked hard to create a simple and easy to understand formula that went through many revisions.

The result?

An organization centered around knowing what you want, visualizing what you want, thinking positively, having gratitude, and seeing what you want come true, all with the spirit of reciprocity (a very important law of The Universe).

Popularized by Napoleon Hill and other authors of self-improvement books for upward-mobile businessmen, “law of attraction” is a magical belief that our thought can transform material reality. In particular, the law teaches that we can make positive material changes in our lives by simply having positive thoughts and attitudes, as positivity attracts positivity, and negativity attracts negativity.

In the “self-help” film “The Secret,” which is based on this theory, author Lisa Nichols explained:

Every time you look inside your mail expecting to see a bill, guess what? It will be there. You’re expecting debt, so debt must show up… Every day you confirm your thoughts. Debt is there because of the Law of Attraction. Do yourself a favor: Expect a check!

In other words, we receive bills because we of our thoughts, not because we have debt. By merely thinking positively, we can receive checks in the mail instead, according to the “law of attraction.”

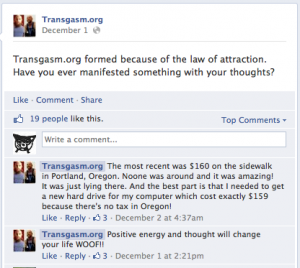

This may sound absurd, but Rose and Angel actually believe in this. For example, they posted the following on their facebook page:

The poster (it’s not clear if it is Rose or Angel) was walking on sidewalk in Portland, thinking how he needed to buy a new hard drive that cost $159 for his computer. Suddenly, because he was being positive, he made $160 in cash to manifest in front of him with his thoughts alone. He happily picks it up, and buys a hard drive. (I’m not sure where the difference of $1 came from.)

Most of us in this situation would not think that we “manifested” the cash with our thoughts. We would assume that the cash fell out of someone’s pocket or wallet, which must have made them sad. Some of us might report the finding to a nearby business or to the police, hoping that whoever lost the money will come and claim it. Some of us might pocket the money. Regardless, most of us do not think that we “manifested” the cash with our own thoughts and therefore we deserve it.

Rose and Angel may have had “good and genuine” intentions to help trans people get what they want, but did not have a sound structure to actually do so. In fact, the structure they envisioned were completely untenable and likely illegal (though details of the scheme was unclear). But if you believe that you can “manifest” cash with mere thoughts, who needs a business plan? There is no reasoning with good-intentioned people with a harmful delusion.

And because Rose and Angel believe that positive thoughts make their project absolutely wonderful and beyond criticism, they perceive any criticism as expression of “hate” and “jealousy”–i.e. negativity. One might wonder why their project would attract so much negativity if “law of attraction” was true, but they purposefully ignore this fundamental contradiction: positivity must attract positivity, and therefore anyone who is negative toward them have to be worst kind of haters. They somehow do not seem to recognize their inconsistent and self-serving application of the principles of “law of attraction.”

I have described “law of attraction” as quintessentially American, because I view it as a variation of the more traditional national ideology of “American Dream.” “American Dream” suggests that anyone can become successful through hard, honest work, which functions to justify extreme income and class inequalities and blame the poor. “Law of attraction” does the same thing, except it doesn’t even require hard, honest work; you only need to think positively. Indeed, “law of attraction” is the “American Dream” for the lazy–and it is fundamentally a regressive, victim-blaming ideology.

Some critics of Transgasm have long criticized Angel for various reasons, but I am not one of them. The reason I become especially alarmed was because of Rose and Angel’s reliance on “law of attraction” in a financial scheme that appeared likely to harm many trans people. I was also alarmed because I know that people who promote pyramid schemes and other scams frequently use “law of attraction” to lure their victims and then blame them for their victimization when their scheme implodes. It has nothing to do with hating them, but I understand that they have difficulty recognizing my (and others’) concerns as long as they use “law of attraction” in a self-serving manner as a shield and weapon against anyone they perceive as “negative.” For now, I am glad that I helped to raise awareness of the danger of their scheme and its ideological foundation.